Exhibit

“Whatever good a woman does outlives her time and services coming ages, like the grain of wheat in fertile soil that store nutrients for the future.”

- May Ziadeh (1924) [1]

Mayy Ziadeh & Arabic Language Media

About Mayy Ziadeh (1886-1941)

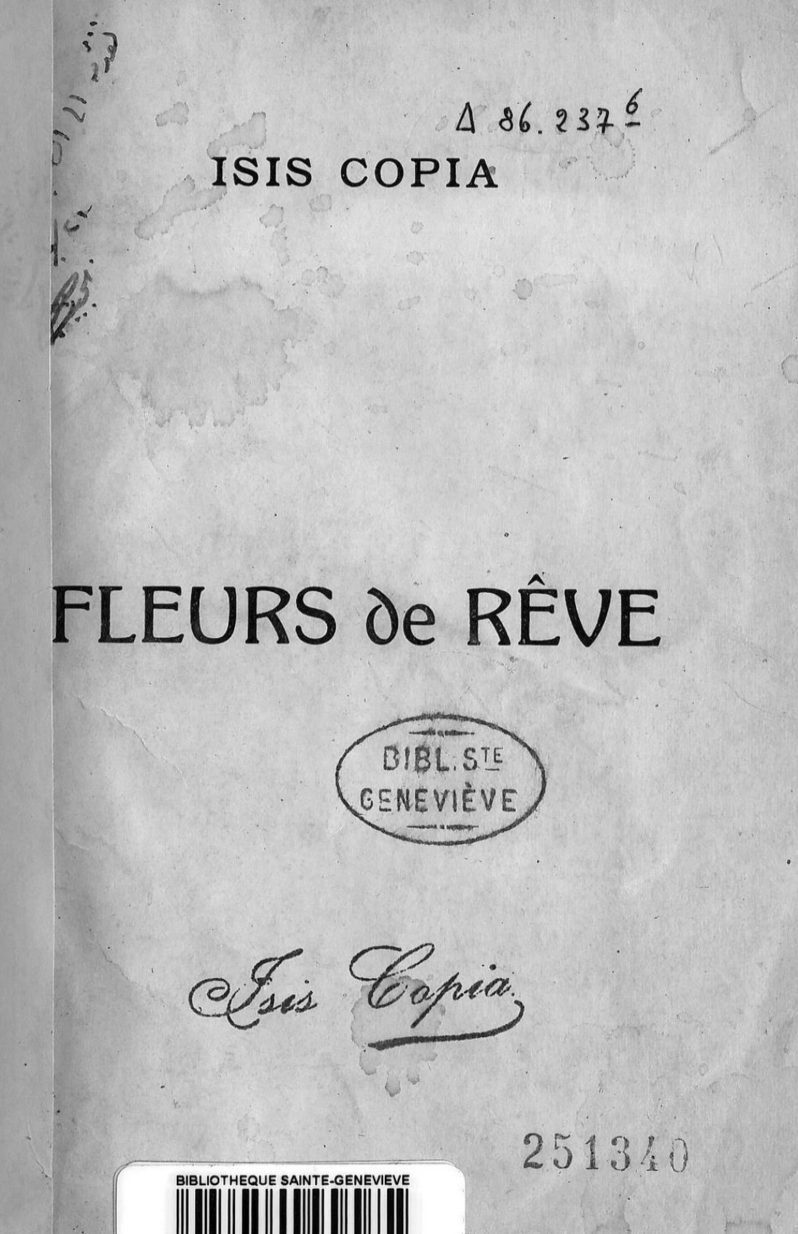

Mayy Ziadeh (birth name Marie) was born in Nazareth, Palestine to an upper-class Lebanese Maronite Christian father and a Palestinian Orthodox Christian mother in 1886 [3]. After completing her primary studies at the Sisters of St. Joseph school in Nazareth (1892-1899), she moved to Lebanon and attended the French Sisters of Visitation boarding school (1900-1903) in the village of Antoora, Keserwan [4]. Mayy Ziadeh moved with her parents to Egypt in 1908 where her journalist father managed the magazine Al-Mahrousa [5]. She wrote articles in Al-Mahrousa and held a central role in developing the magazine [6]. She published her first book, a poetry collection written in French, titled Fleurs de Rêve (Dreamy Flowers) in 1911, under the pseudonym “Isis Copia” [7]. She translated some of her poems to Arabic under the name “Aida”.

In an environment in which writers were pushing for the expansion of Arabic language, as part of the Arab Nahda/renaissance, Mayy Ziadeh switched to writing in Arabic instead, and began using the Arabic name Mayy in-place of her birth name, Marie. In 1911, Mayy wrote her first article in Arabic after attending a lecture on women’s liberation delivered by feminist Labiba Hashim in Egypt [8]. Her decision to write in Arabic would lead her to become an important contributor to the Arabic language movement. Her work was critical, not only because of her Arabic mass-media cultural contributions and writings, but also because she enriched the written record by giving language to a struggle of which the masses did not have the media literacy and means to widely and multi-lingually express. Amongst her many achievements, Mayy Ziadeh wrote books on other famous Arab women writers and eulogized them in the media after their death [9]. She hosted a literary and cultural salon in her Cairo home between 1913 and 1930.

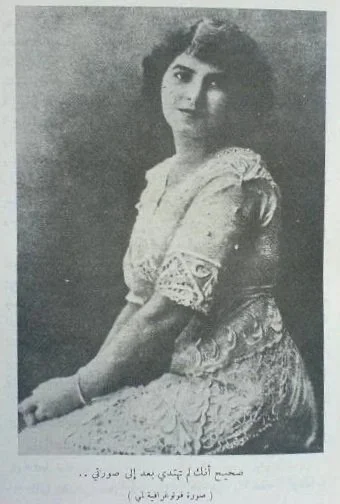

A portrait of Mayy Ziadeh. This image was first circulated in the press in 1922 [2].

On May 16, 1936, Mayy Ziadeh’s paternal cousin, Joseph Ziadeh, forcibly admitted her into the ‘asforiyya’ sanatorium in Beirut, in a conspiracy to take-over her assets in the years following the death of her parents [10] In defiance of the conspiracy against her, Ziadeh went on hunger strike and a protest campaign was launched in support of her by Haifa-based al-Karmel [11] Newspaper editor Abdallah Mukhles, Fouad Hbeish, editor of the Beirut-based al-Makhsouf, and writer Amin al-Rihani [12]. Ziadeh remained in and out of hospitalization until February 14, 1938 when her efforts to break free succeeded and she delivered a lecture at the invitation of the Beirut-based Arab nationalist group, ’Al-oo’rwa Al-wothqa’, before moving back to Egypt [13].

Mayy Ziadeh’s Lecture in the Al-oo’rwa Al-wothqa celebration at the American University in Beirut. It was held on the evening of Tuesday, March 22, 1938. AUB Jafet Library Special Collection, Mayy’s Ziadeh’s Folder, 1920s-1930s, Catalog ID: b26287407, Call No.: A.892.1.

In a 1938 letter to her nurse Esther Wakim, Mayy describes how her friends deceived her. “They came to me in Egypt in my sadness to tell me: ‘Mayy, travel to Lebanon, your family is there,’” she writes. But once in Lebanon, she was “carried to the insane asylum … where I tasted death several times.”

Excerpted from: Ziadeh, Mayy. May’s Letters (رسائل مي). Presented by Jameel Jabr, Dar Beirut Publications, 1954, 94.

In an undated letter to “A Friend,” Mayy Ziadeh explains her decision to go on a hunger strike. She writes that she longed for death after her library and furniture were sold at public auction, a loss that symbolized the stripping away of her intellectual and personal world. She also refused visitors, noting that those who came spoke to her as if she had lost her sanity.

Excerpted from: Ziadeh, Mayy. May’s Letters (رسائل مي). Presented by Jameel Jabr, Dar Beirut Publications,, 1954, 93.

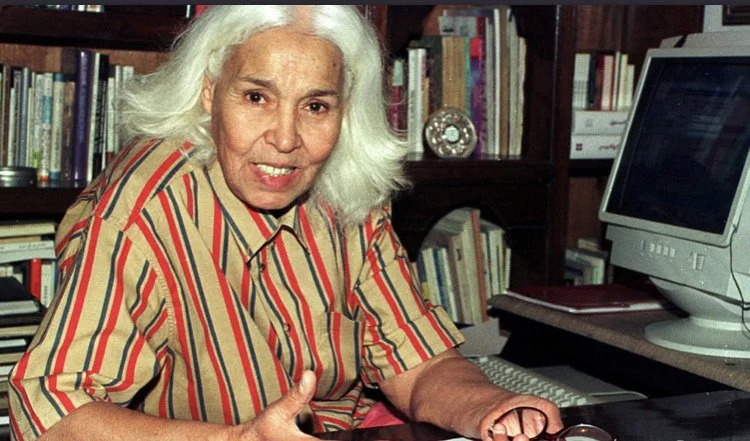

Mayy Ziadeh’s last public lecture was titled ‘Live Dangerously’, and was presented at the American University in Cairo (January 20, 1941) [14]. A few months later, Mayy Ziadeh died at the age of 55 at the Al-Maady Hospital in Cairo on October 19, 1941 [15]. The late feminist writer’s funeral and memorial service was organized by Huda al-Shaarawi, president of the Egyptian Feminist Union (EFU) [16]. The EFU led a procession and a large memorial in honor of Mayy Ziadeh at the Feminist Union’s headquarters in Cairo [17]. Mayy Ziadeh’s influence was threatening to the patriarchal system in which she lived. In a 1999 article published in the Egyptian Rose al-Yousef, [18] Nawal El-Saadawi reflects on Mayy Ziadeh’s life and writes about the courage that she must have had to be able to achieve and endure all that she did in her life as a journalist, orator, and feminist. El-Saadawi describes the guests of Mayy’s salon as betraying her in her time of crisis, in which few of them did anything to support her during her forced hospitalization.[19] She also describes Mayy Ziadeh’s final days in Cairo as filled with public lectures, growing stardom, and determined independence, as she refused to meet with those that abandoned her during her time of need.

It has been proven that Mayy Ziadeh’s soul was not sick, her brain was not sick, on the contrary, she possessed a rare and great talent […] she refused to be a slave to femininity and motherhood, and this is how she was able to leave behind a literary treasure more important than if she had birthed three men. [20]

El-Saadawi explains that patriarchal greed and envy underlie Mayy’s forced isolation [21]. A street in Beirut is named after her and a statue of her is placed in the village of Keserwan, where her father was from and where she attended school [22]. She is remembered as one of the “most important Arab women writers in the first half of the twentieth century.” [23]

Mayy (center) leaving asforiyya’ sanatorium in Beirut in 1938. Source: Naccach, Nessrine. May Ziadé, pionnière téméraire du féminisme oriental (May Ziadé, daring pioneer of Eastern feminism). 2019.

Gallery

This gallery offers photographs and letters related to Mayy Ziadeh. Portraits of Mayy included here are some of the only recorded photographs we were able to find of her.

An image Mayy sent to Julia Dimashqiya, writing beneath it: “It is true that you have not found my picture yet … (A photographic image of Mayy)”. Source: “May Ziadeh's Rise and Fall: Her Life - Her Personality - Her Literature - Her Art” by Rose Ghorayeb. Nawfal Institute, 1978.

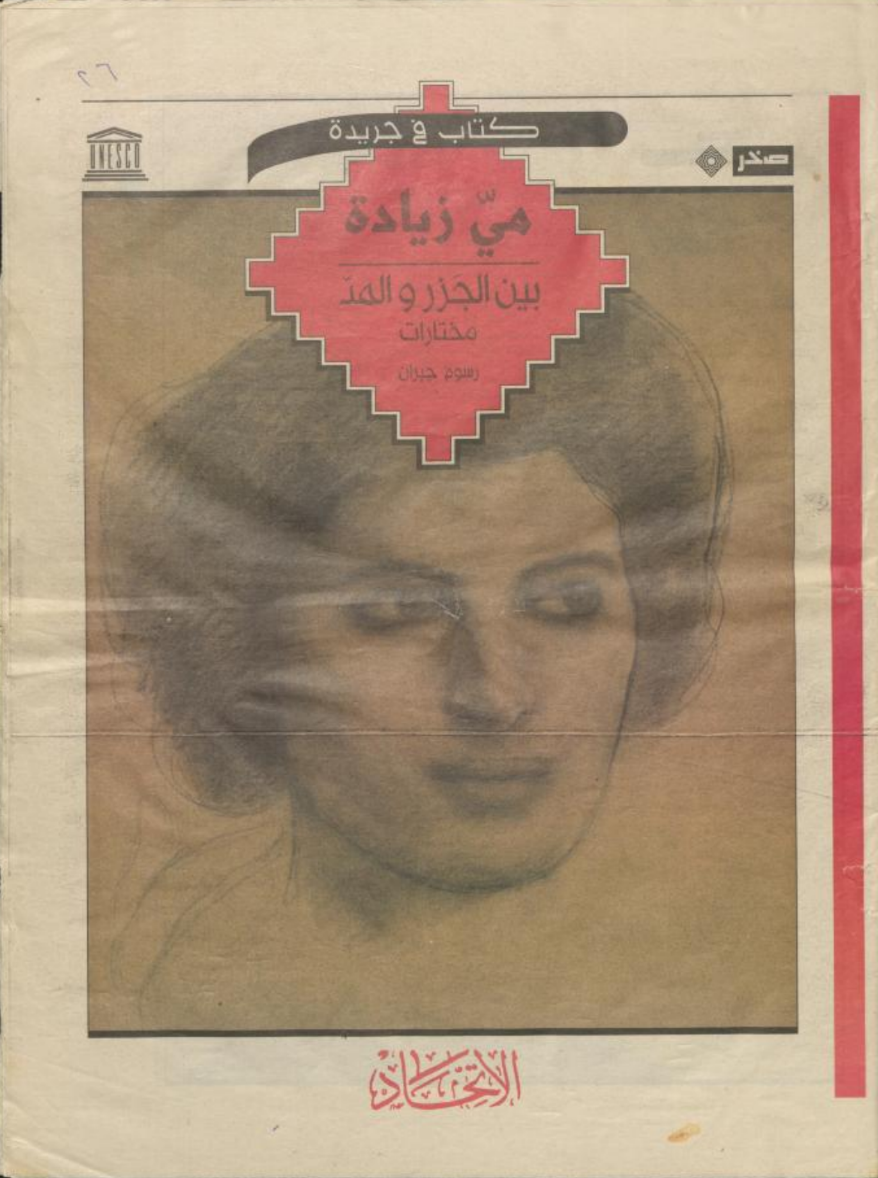

Mayy’s portrait, drawn by Jibrane Khalil in "May Ziadeh In the Tide", a Pamphlet by al-Ittihad Newspaper, 1998 -2000., Ozrail, Samar. Karaja, Aysha. "The Shakib Jahshan Collection. Archival Inventory. 28 June 2022. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive.

Mayy as an infant with her mother in Al Nassirah, Palestine, 1889. Source: Naccach, Nessrine. May Ziadé, pionnière téméraire du féminisme oriental (May Ziadé, daring pioneer of Eastern feminism). 2019.

A portrait of Mayy. Image found in Al Youm Al Sabe’ Magazine, published on 20 October 2021.

Image of Mayy in “Remember Mayy Ziadeh” a pamphlet published by Alwadisya for Culture and Media in November 1999. AUB Jafet Library Special Collection, Mayy’s Ziadeh’s Folder, 1920s-1930s, Catalog ID: b26287407, Call No.: A.892.1.

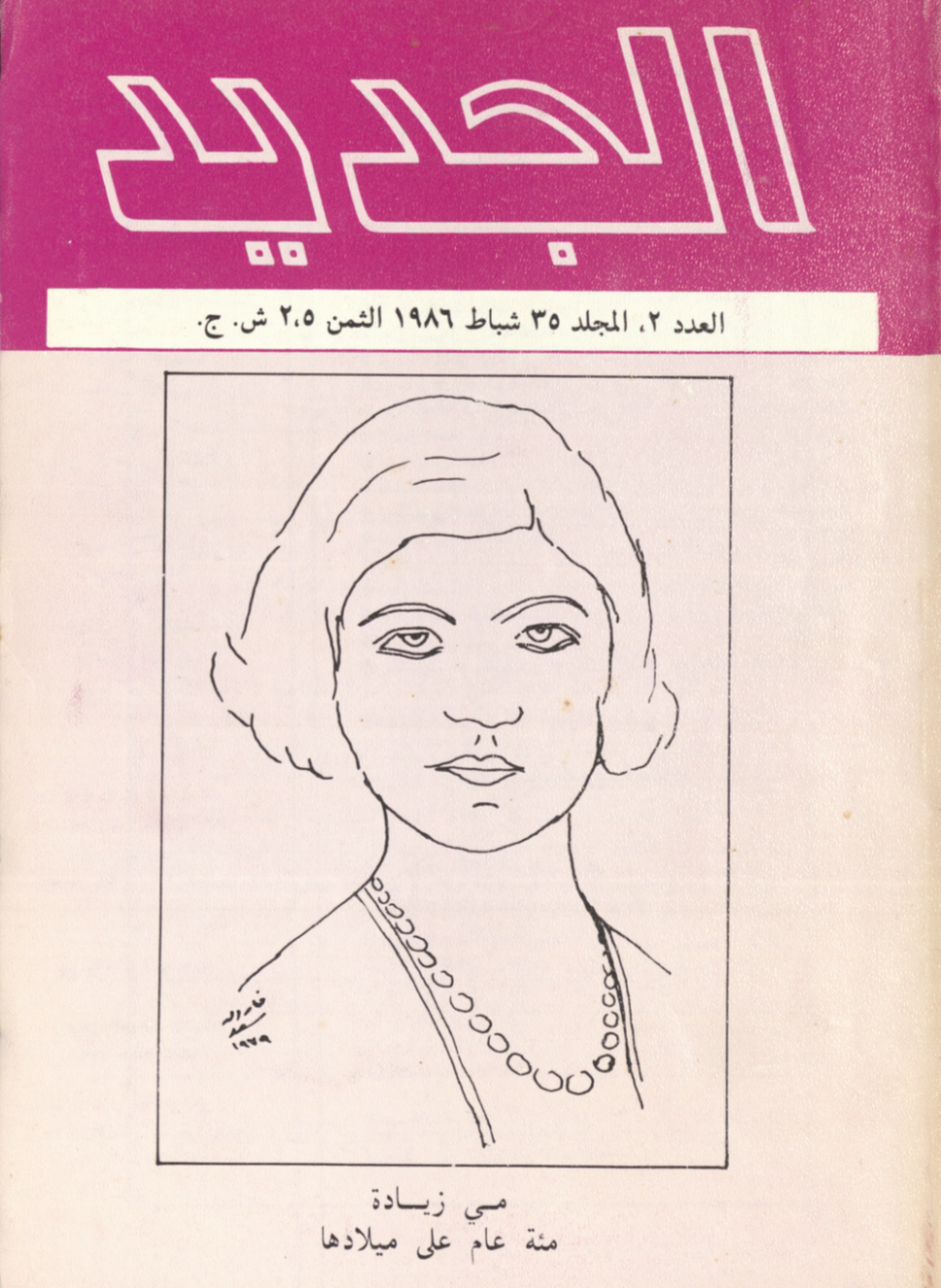

Mayy on the cover of AlJadeed Magazine Vol. 2 Issue 35 published in February 1986.

The late feminist Huda al-Shaarawi speaking at Mayy Ziadeh’s funeral that was held on 20 Ocfober 1941 in the Maronite Church in the Shubra neighborhood. Image found in Al Youm Al Sabe’ Magazine, published on 20 October 2021.

Image of the attendants at Mayy’s funeral. Image found in Al Youm Al Sabe’ Magazine, published on 20 October 2021.

In a letter to Jabir Dumit, a writer, journalist, and professor at the American University of Beirut, Mayy Ziadeh expresses her endorsement of co-education for both personal and social reasons. In the same letter, she thanks him for his positive review of her book Bahithat al-Badiya. AUB Jafet Library Special Collection, Mayy’s Ziadeh’s Folder, 1920s-1930s, Catalog ID: b26287407, Call No.: A.892.1.

“I was born in a country, and my father is from a country, and my mother from another country, and I live in a country. The ghosts of my soul move from one country to another, so to which of these countries do I belong? Which of these countries do I defend? […] I have not spoken of the bravery and virtue of a nation without longing for it as my own […] I kneel in humility in remembering you [philosophers] and say “All I desire in life is a homeland to die for or to live in.”

- May Ziadeh in an article entitled, Where is My Homeland? [24]

Mayy and Arab Feminist Collegiality and Conciousness

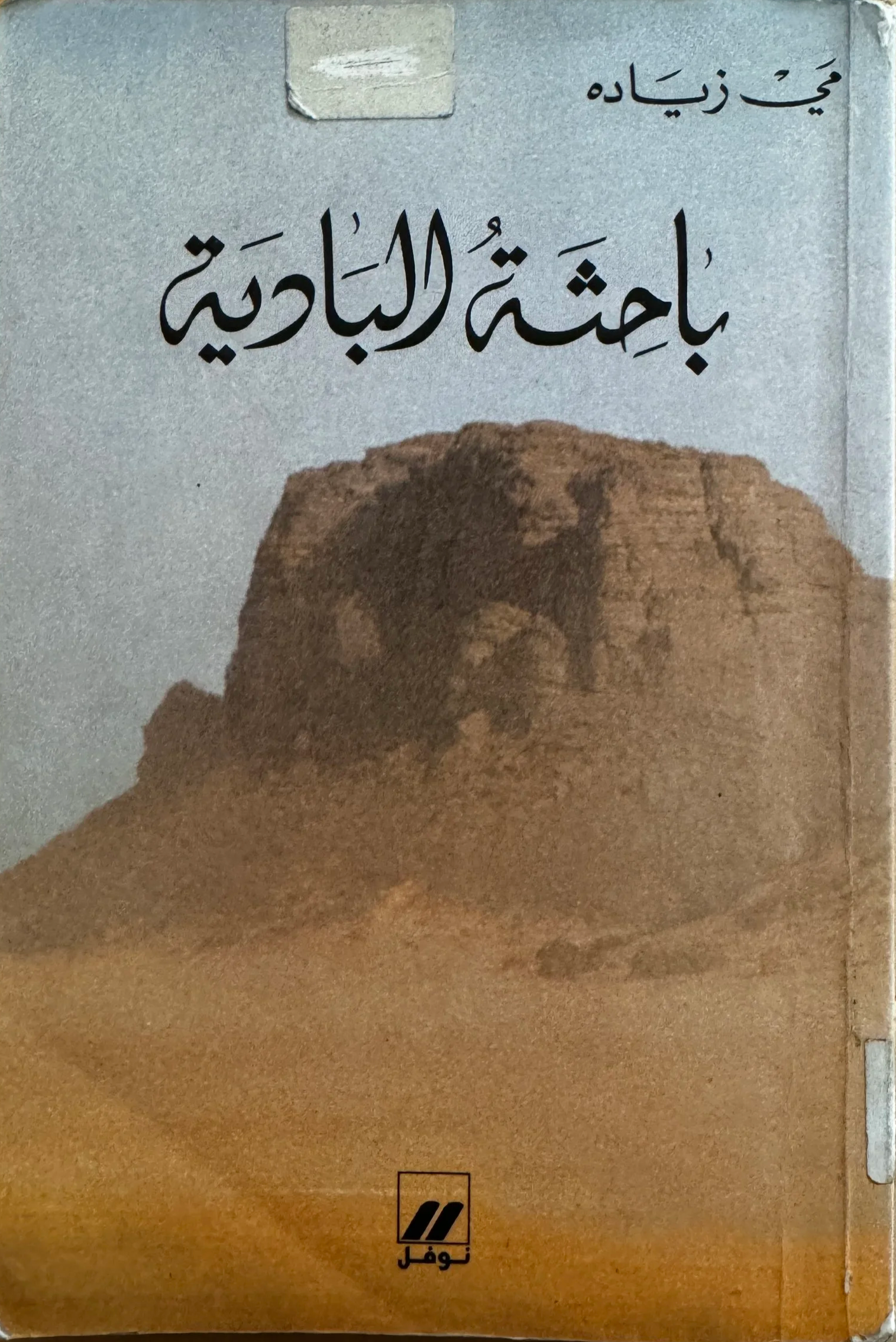

A large portion of Mayy Ziadeh’s work includes biographies of Arab women writers. Her first book authored in Arabic is a biography of the Egyptian woman writer and educator Malak Hifni Nassif (1886-1918), also known as Bahithat al-Badiyya (Scholar of the desert) who Mayy Ziadeh admired [25]. Having expressed her love for Nassif’s earlier writings in a letter in which she (Mayy) told Nassif that her (Nassif’s) works are “still waiting for somebody to unravel its secret” [26], Mayy Ziadeh unravelled Nassif’s ideas by producing the biography Bahithat al-Badiyya. Mayy Ziadeh and Malak Hifni Nassif had a close relationship of correspondence in which they discussed the deep struggles of their intimate nationalist and feminist sufferings and published their correspondences [27]. As Nassif references in her book al-Nisa’iyyat (Relating to Women), in a letter Ziadeh writes to her [28]:

ما أطيب قولك، يا سيدتي الباحثة، إنك تشفقين على من يستحق الشفقة ومن لا يستحقها! الرجل من الذين يستحقون الشفقة؛ لأنه لا يعرف أنه يستحقها إنه باستعبادنا لمنتحر

Dear Desert Seeker [29], how fine your words are! You feel sympathy for those who deserve sympathy and those who do not, man deserves it because he does not know that he deserves it. Indeed, [30] by enslaving us he is committing suicide. [31]

The collegiality demonstrated in women’s intimate letters to each other on the topic of feminism and men’s subjugation was one of the ways that Arab feminist thought entered the public arena. The ideas that Mayy Ziadeh presented in her Arabic and French articles in magazines such as Al-Moqattam, Al-Ahram, Al-Zohoor, Al-Mahrooseh, and Al-Hilal gathered the attention of the literary community in the Arab world, including in feminist circles [32].

Bahithat Al-Badiya

The 1913 letter to Bahithat al-Badiya, Mayy praises her contributions to women’s intellectual and social awakening, encouraging her to continue advocating for education and the liberation of women. It highlights the shared struggle for progress across the Arab world, expressing hope that women’s empowerment will lead to national renewal and societal strength.

In this undated letter to Mayy, Malak Hifni Nasif encourages Ziadeh to persist in her efforts to elevate Arab women intellectually and socially, stressing the importance of education and deep social engagement as foundations for true liberation. She frames women’s contributions and their liberation as essential to the broader project of national justice.

A portrait of Malak Hifni Nassif in Mayy’s book Bahithat Al-Badiya (1920) [33[

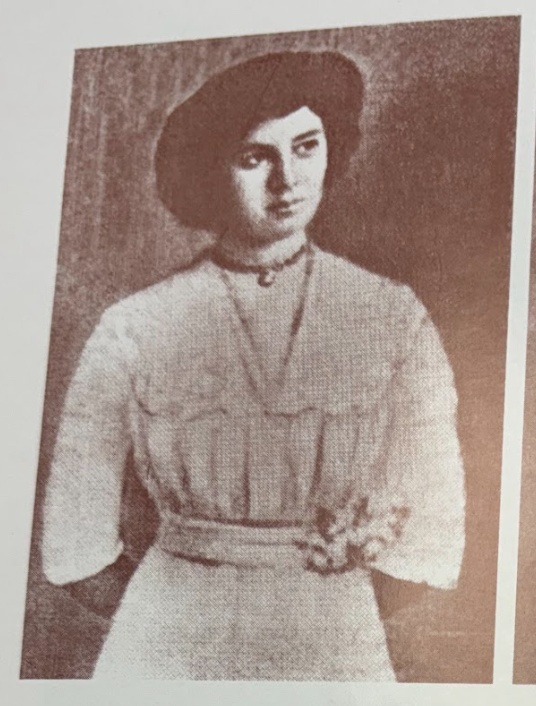

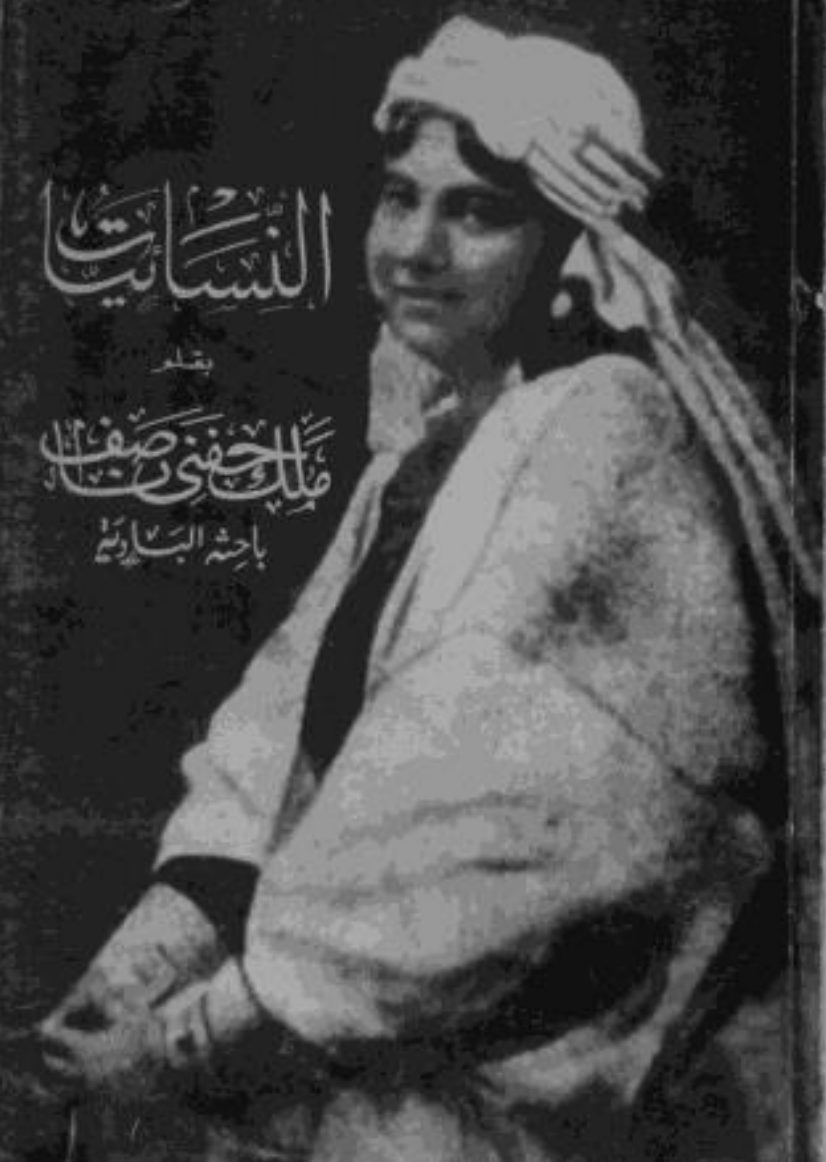

Malak Hifni Nassif on the cover of her book Al-Nisa’iyyat (1910) [34]

Warda Al-Yaziji

In 1924, Ziadeh published a biography of the poet Warda al-Yaziji after the Shami Egypt-based poet’s death [35]. Like Mayy Ziadeh, Ward al-Yaziji lived for a long period in Egypt and died there [36]. The biography includes a eulogy that Mayy Ziadeh published in the popular magazine al-Muqtatif. In 1999, Margot Badran and Miriam Cooke translated selected excerpts from Warda al-Yaziji in their anthology of Arab women’s writings, Opening the Gates [37]. Warda al-Yaziji came from a very similar background as Mayy Ziadeh as they both worked in the field of Arabic literature and lived their lives as both Lebanese/Syrian and Egyptian [38]. Ziadeh writes in her book:

“May you retain a memory that endures beyond this meeting. May everyone be reminded by her that whatever good a woman does outlives her time and services coming ages, like the grain of wheat in fertile soil that store nutrients for the future.”[39]

Ziadeh says that we must recognize how those that came before us have opened up the way for us. And she stresses that by “‘Open up the way’, all they did was “put up a signpost at the threshold of unknown territories. However, this signpost has value and use, especially when we remember when it was put up” [40]. In picking the grains, sharing, and spreading and working together, we pick up sign posts and perhaps, try to place and share a few on the way. These signposts however, sometimes become displaced, buried under the rubble of destruction or stolen and re-packaged and sold to us. Yet, they remain and here we are.

الشرق ينهض، أيتها السيدات، وهنيئًا لمن أدرك كل ما في المسئولية من فخر، وكل ما في العمل من نصر. الشرق ينهض ولو كانت جباه رجالهِ مثقلة بالأحزان، وجماعات من شبيبتهِ منصرفة إلى اللهو والنسيان! الشرق ينهض، وهنيئًا لكل من كان بعملهِ وقلمهِ وصوتهِ ذا أثر في تكييف النفوس! وهنيئًا لطلاب العلم بالممكنات التي يتمتعون بها ممتازين بذلك عن كل جيل سبقهم؛ لذلك كان ما يُنتظر منهم أعظم من كل ما جاء بهِ غيرهم.

The East is rising, ladies, and congratulations to those who understand the pride in responsibility and the victory in work. The East is rising, even if the foreheads of its men are burdened with sorrows, and groups of its youth are distracted by amusement and forgetfulness! The East is rising, and congratulations to everyone whose work, pen, and voice have an impact on shaping minds! Congratulations to the students of knowledge for the opportunities they enjoy, distinguishing them from every generation before them; therefore, what is expected of them is greater than what anyone else has achieved.

-Mayy Ziadeh, in commemoration of Warda Al-Yaziji as written in her book about her [41]

A portrait of Warda Al-Yaziji. [42]

Solidarity with Egyptian Women

In a 1923 letter to The Egyptian Woman, Mayy Ziadeh urges young women to recognize the power of choice in shaping their futures. She contrasts two paths: the “slave,” marked by idleness and gossip, burdening family and society; and the “queen,” defined by discipline, honesty, hard work, and kindness, uplifting home and nation. She closes by asking: which will you choose?

Source: "Rasa'l Mayy" (From Mayy's Letters) by Jamil Jaber. Manshourat Maktabat Beirut, 1951.

Letters to Huda al-Shaarawi

Mayy Ziadeh’s letters to Huda al-Shaarawi further demonstrate her engagement with fellow Arab feminists, expressing admiration for al-Shaarawi’s leadership and commitment to women’s causes. In these exchanges, she affirms her support for the feminist community and celebrates the efforts of peers in amplifying women’s voices.

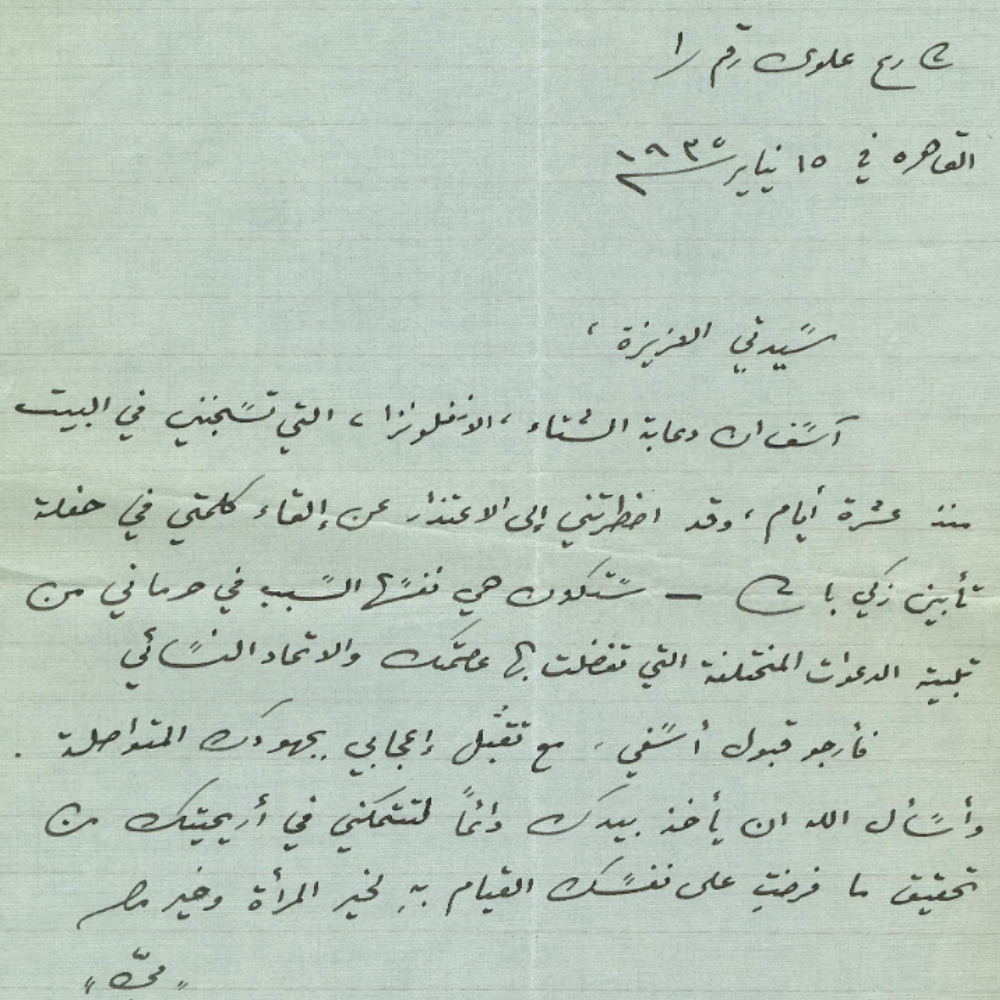

Letter to Huda al-Shaarawi on 15 January 1935 where she apologizes for declining multiple feminist union invitations including a memorial because she had the flu. Mayy also extends her appreciation for Huda’s efforts in feminist unions. “Letter and Correspondences" Huda al-Shaarawi archive - American University of Cairo Special Collections.

Letter to Huda al-Shaarawi dated 14 April 1927, in which Mayy acknowledges receiving her speech and expresses pleasure at the invitation to join the feminist community. She affirms her support for Huda in heart and soul, notes that her name had appeared on a list of notable literati, and praises al-Shaarawi’s efforts to amplify women’s voices. “Letter and Correspondences" Huda al-Shaarawi archive - American University of Cairo Special Collections.

Books

This gallery is a collection of books about Mayy Ziadeh and books she’s written. If you wish to learn more about the contents of a specific book or wish to request excerpts, please contact us.

Copia, Isis (pseudonym of Mayy Ziadeh). Fleurs de rêve, 1911.

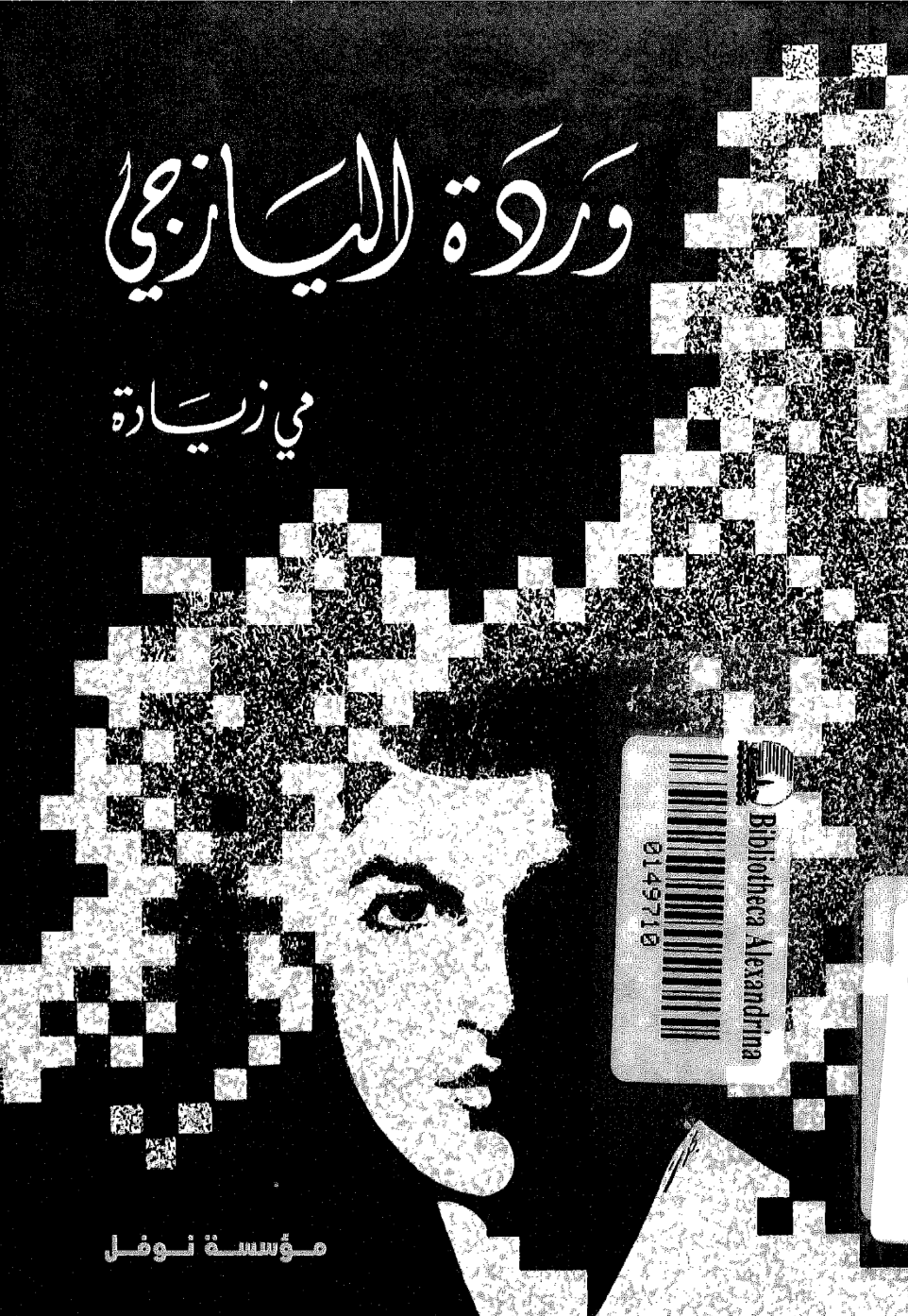

Ziadeh, Mayy. Warda al-Yaziji (وردة اليازجي) Nawfal Institute, 1924. Reprint: 1980.

Ziadeh, Mayy. May’s Letters (رسائل مي). Presented by Jameel Jabr, Dar Beirut Publications, 1954.

Rihani, Ameen. My Story with May (قصتي مع مي). The Arab Institute of Studies and Publications, 1980.

Ziadeh, Mayy. Bahithat al-Badiya: A Critical Study (باحثة البادية: دراسة نقدية). Nawfal Institute, n.d.

Al-Kuzbari, Salma al-Jaffar. Mayy Ziadeh and the Media of Her Era (مي زيادة واعلام عصرها). Nawfal Institute, 1982.

Al-Qawall, Antione. Texts Outside the Collection: Mayy Ziadeh (نصوص خارج المجموعة: مي زيادة). Dar Amwaj, 1993.

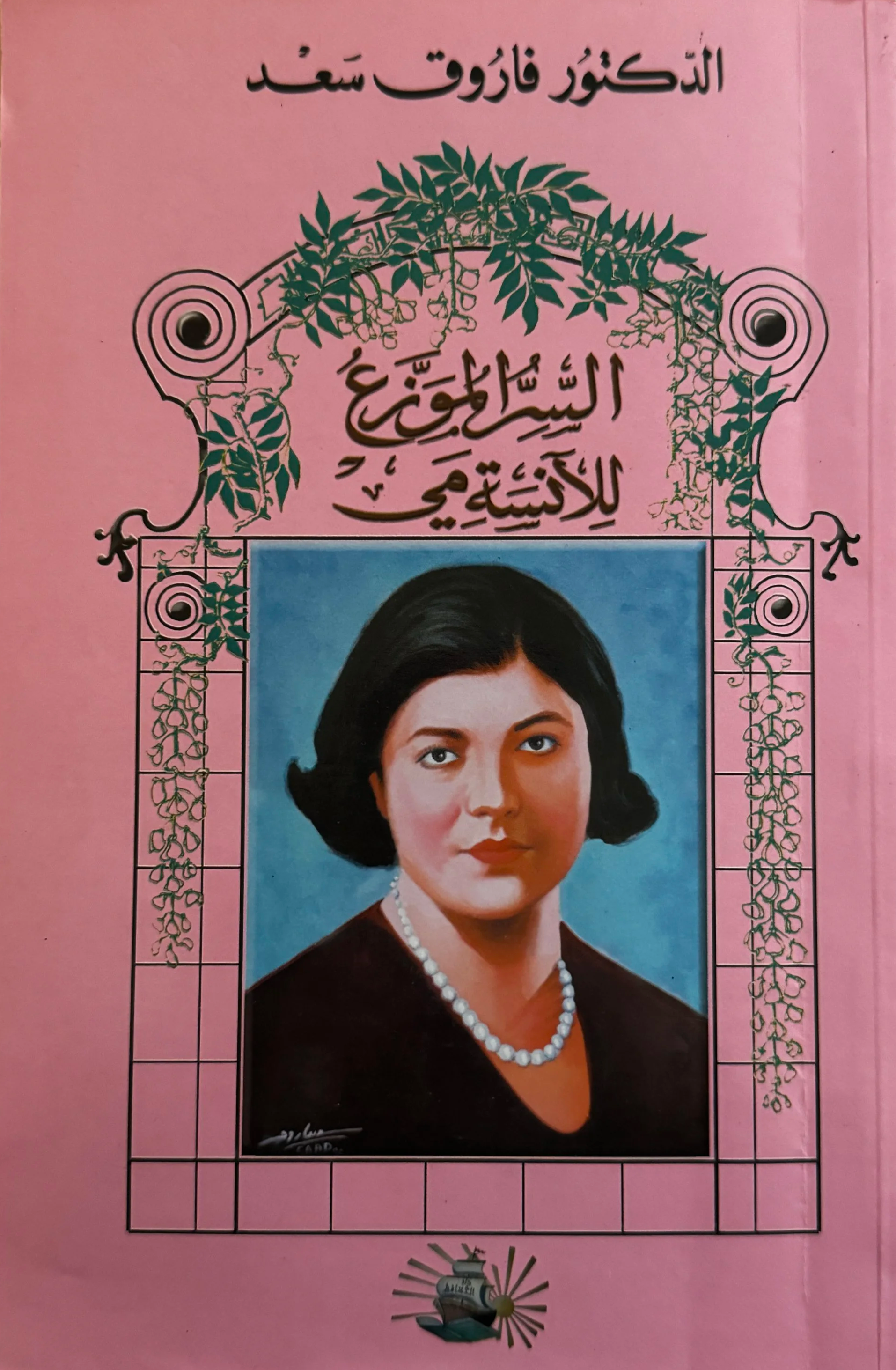

Saad, Farooq. The Secret Distributed to Miss Mayy (السر الموزع للانسه مي). Dar al-Thaqafa for Printing, Publishing and Distribution, 2003.

Ziadeh, Mayy. Forgotten Writings (كتابات منسية). Edited by Antje Zeigler, Nawfal Institute, 2009.

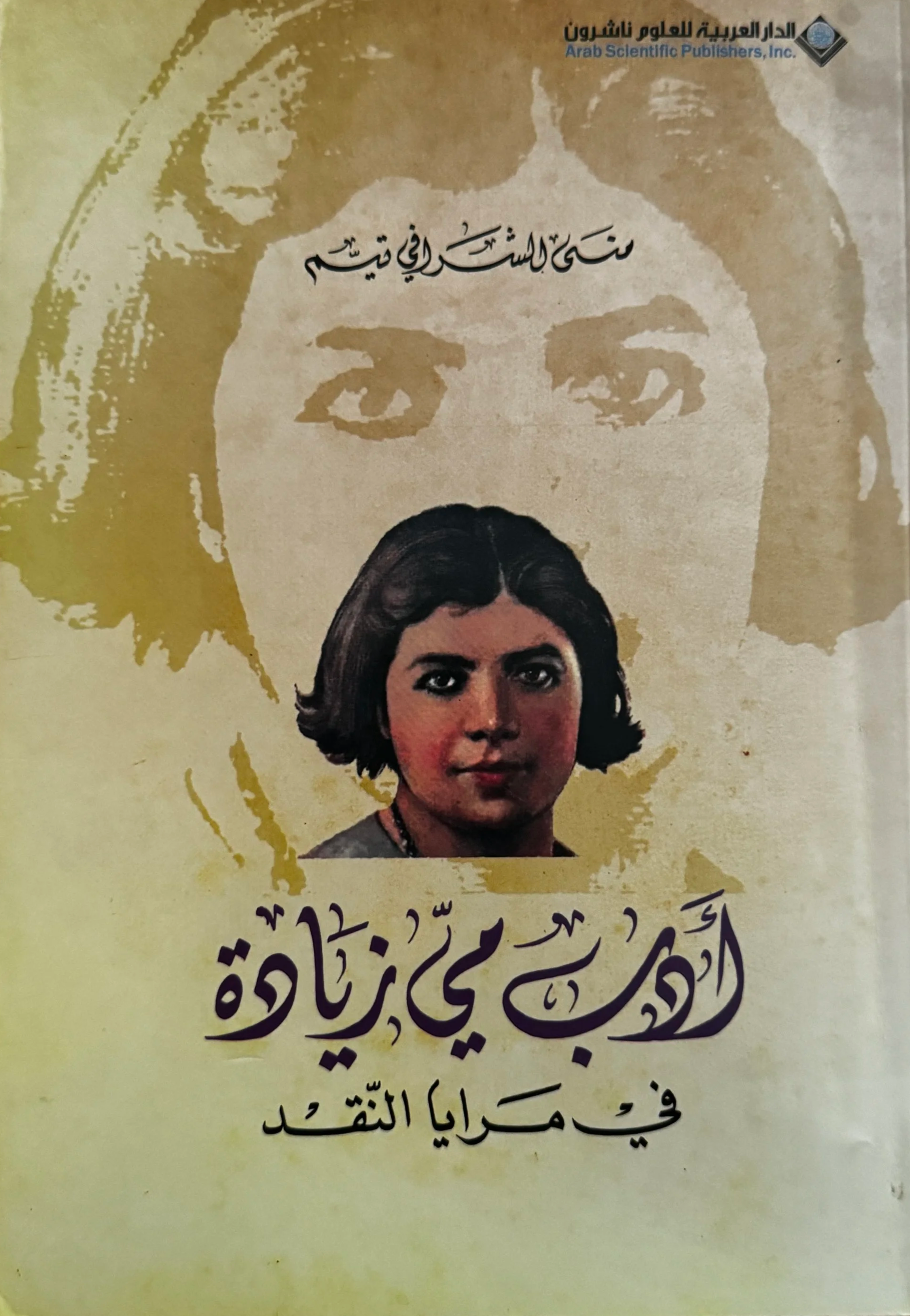

Tayyim, Muna al-Sharafi. May Ziadeh’s Literature in the Mirrors of Criticism (أدب مي زيادة في مرايا النقد). Arab Scientific Publishers, 2010.

Journalism and Literature

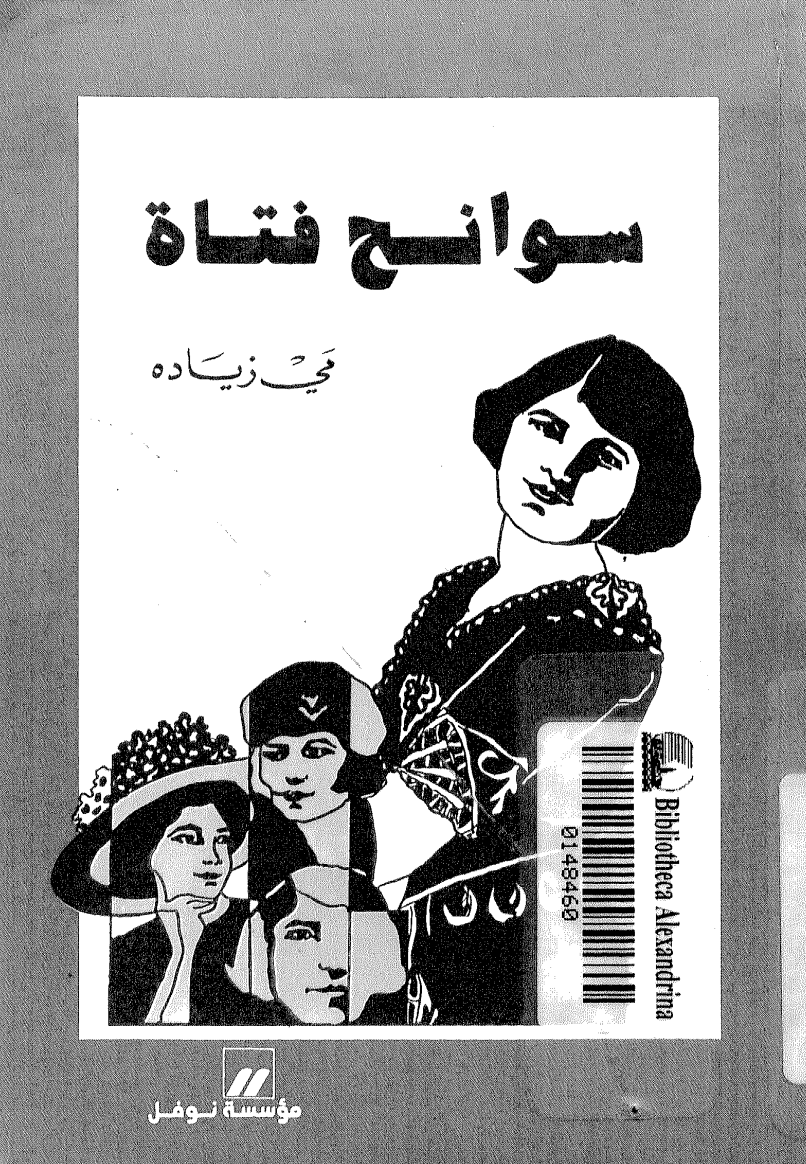

Mayy Ziadeh believed that all journalists must understand the significance of the relationship between literature and journalism wherein the two are ‘one’. This relationship is critical for understanding the depth of Arab feminist involvement in the development of early twentieth century Arab press. Mayy Ziadeh adopted different forms of communications as a feminist method, and she is therefore not only a writer but a media practitioner and journalist. In her 1922 book Sawanih Fatah (A Girl’s Memoir), Mayy Ziadeh includes an article dated 1916 and titled, “Literature and Journalism.” [43] In the article, she describes a scene in which she was sitting in an audience listening to a lecture delivered by the British literature professor at the Egyptian University, Percy White [44]. In the lecture, White was speaking on the difference between literature and journalism in which White asked, “Are literature and journalism one?” Answering himself, White dedicated the lecture to the claim that “no, they are not one, literature is of a higher meaning and beauty, and its effect deeper, whereas journalism has different goals, impact and purpose.” [45] In response to this, Mayy Ziadeh writes:

Ziadeh, Mayy, Sawanih Fatah. Nawfal Institute, 1922. Reprint.

بينما كان الأستاذ يبسط رأيه كنت أضاحك نفسي قائلة: قد يكون هذا رأيكم أيها الغربيون، لكن الأمر عندنا على غير ما تذكرون؛ عندنا إذا كتب المرء مقالات قليلة في الزراعة مثلًا، حاز دفعة واحدة جميع الألقاب الكتابية المدوَّنة في القاموس فأصبح: كاتبًا مجيدًا، أديبًا أريبًا، مفكرًا مبتكرًا، شاعرًا فذًّا، خطيبًا مفوَّهًا، سياسيًّا محنكًا، عالمًا علَّامة وبحرًا فهَّامة

While the professor was explaining his opinion, I was laughing to myself, saying: this may be your opinion as Westerners, but our situation is different from what you describe. For us, if a person writes a few articles in the field of agriculture, for example, they gain many titles at once, they become a glorious writer, a wonderful intellectual, an innovative thinker and an outstanding poet, an articulate orator, a seasoned politician, and a scholar. [46]

As Ziadeh shows in the article, in the context of twentieth century Arab media, varying forms of communications hold similar cultural importance and influence. Her point to reference the field of “agriculture” in her discussion about literature and journalism, further brings to the forefront the material fact of the Arab struggle for self-determination as tied not only to knowledge, but also to land and its liberation. Mayy writes that the Arab writer, no matter the genre, is celebrated as an “innovative thinker”, she brings to the forefront the value of the variety of Arab knowledge as an interconnected set of liberatory practices. Mayy refers to the infrastructural material conditions of the Arab press in making her argument against the binary between journalism and literature:

على أن خدمات الصحافة جليلات ولا غنى لأمة متمدنة عنها. ولصحافتنا العربية مزية خاصة في هذا العصر بكونها لسان حال الأدباء والعلماء والمفكرين والمتشرعين. كتب العلم والأدب قليلة عندنا؛ لأن علماءنا وأدباءنا قليلون. وقد ندُر بينهم مَن استطاع تأليف كتاب والإجادة التي هي شرط الإفادة

However, press services are great and are considered indispensable to any cultured nation. And our Arab press has a special advantage in this age by being expressive for writers, scholars, thinkers, and legislators. Books of sciences and literature are few amongst us, because our scholars and writers are few. It is rare amongst them who is able to compose a book and without proficiency, a requirement in this case, its effects are decreased. [47]

Ziadeh, Mayy, “Bayn al-adab wa al-sahafa” (Between Literature and Journalism) in Sawanih Fatah, 33-37.

First page of Ziadeh’s magazine, Al-Mahrooseh. It reads beside the title: “Correspondence is sent under the name of the owner of the magazine and Editor-in-Chief Miss Mayy Ziadeh”. [48]

AL-Mahrooseh was created in 1875 and many famous writers wrote in it, including: Salim Effendi Al-Naqqash, Girgis Effendi Al-Naqqash, Sheikh Muhammad Abduh, Adeeb Bey Ishaq, Ibrahim Effendi Al-Hourani [49]. The magazine was first published by Saleem Naqish in Alexandria, and it later was moved to Aziz Zend in Cairo, and then Elyas Zyadeh, Mayy’s father. Mayy started editing the magazine after her father passed away in 1929. The first article she published after his death was on November 20, 1931 (Issue 4924) and it was titled “Death and Suicide”.

The opening poem written on the first page of Al-Mahrooseh in the first issue after it was owned by Elyas Zyadeh, published on 11 January, 1909 in Cairo [50]. It celebrates the newspaper’s revival under new ownership, praising its enduring legacy, its protection from harm, and its commitment to truth.

In Mayy’s account of an unnamed public figure, she describes her frustration when a fellow Arab public figure was adamant on speaking to her in French:

…this public figure forgot that I am an Arab and I write in Arabic and he chose to speak to me in French instead and he insisted on doing so although all my answers to his questions were in Arabic. […] He should understand that I am not European. I am an Arab. He should have spoken to me in Arabic only. [51]

On the Arabic Language

Mayy understood the imbalance in the availability of foreign language and Arabic books, in addition to the Western gaze, as a detriment to the Arab press and cultural production. It is important to note that while she is critical of the presence of foreign writers in the Arab world, Mayy nonetheless advocated for a constant engagement between Eastern and Western knowledge [57].. Her point to signal to the importance of “examination between the foreign writer and us” is that we examine them in the context of our own “eastern environment.” [58] This understanding and point of examination is reflective in Ziadeh’s own writings in which she regularly engaged with French, English, German, and other European and American writers’ ideas in her work. Her deas on the state of Western knowledge and gaze in the Arab world and the importance of building Arabic knowledge is a culmination of her life’s experience as a French-educated writer who mastered the Arabic language at an older age [59]. She was a strong advocate for the Arabic language. Even though, at least in her earlier years, it was significantly easier for her to write in French, in the early 1910s, at around the age of twenty-five, Ziadeh committed herself to writing in Arabic:

If most of the time I express myself in a Western style, it is because my education and readings were in foreign languages, and if I am to be blamed for not mastering Arabic as I should have, I think being new to Arabic is an acceptable excuse particularly because I learned it through listening and desire […] I took an interest in it because I am an Arab. The Nahda of the Arab blood flowing in my veins call my attention to the love of the language and to a desire to use it to express the crowded ideas in my mind. [60]

Mayy’s early education took place in French missionary schools in Palestine and Lebanon, where Arabic was sidelined and in favor of French language. During her twenties, May made a conscious decision to write only in Arabic, reclaiming the language as a core part of her identity and work. While she was not required to take up Arabic in her media practice, her commitment to learning and using Arabic is one marked by giving “attention to [her] love of the language” and by her consideration of Arabic as a core part of her identity, as opposed to the French cultural identity that was forced upon her during her youth in the missionary schools. [61]

Ziadeh’s identity was not fixed to clear boundaries, rather, her sense of self and belonging was drawn from evolving and varied cultural and geographical influences. The Arabic language was the connecting force between the multiple places which she considered home. The theme of cross-regional solidarity which exists in much of her writings was stemmed from this core feature of her identity as a “daughter of two cotenants.” Within this tradition, Mayy Ziadeh’s feminism was based on advocating for an environment in which women felt welcomed to join forces with each other [62]. Mayy references the significance of marking these connections between women’s achievements across time and place as a prerequisite for achieving liberation. As she shows in much of her writing, Mayy advocated for the commemoration of women’s history, writing and achievements. She writes, : “And like them I [cheer] enthusiastically, and, following their examples, I [move forward], for knowledge and for the good of [homelands]! [63]

Image of Mayy behind her desk in her house’s salon in AlMaghribi Street in Cairo,. “Miss Mayy’s Secret” written by Farooq Saad. Dar Al Thaqafa for Printing, Publishing and Distribution, Beirut, 2003.

In 1913, Mayy Ziadeh began hosting her “Tuesday salon,” a weekly event that lasted 20 years, in which writers, people of letters and intellectuals, would gather to discuss a wide range of topics [52]. Ziadeh made a point of inviting journalists and encouraged people to publish stories about their experiences in the salon in newspapers and magazines [53]. One of her dedicated guests, Egyptian writer Taha Hussein, declared about Ziadeh’s salon: “Mayy’s salon was democratic, in the sense that it was open to various classes of intellectuals and to literary men and women of different nationalities.” [54] In her book on the topic of Mayy Ziadeh’s salon, Boutheina Khaldi describes Mayy’s public contributions as “forums where justice, equality and free speech were discussed and pursued.” [55] She implemented a strict language policy at her Tuesday Salons in which only the Fusha (formal) Arabic dialect was allowed, while she deeply discouraged the use of foreign language and “al-ammiyya” [56] (informal dialect that varies according to geographical areas).

Mayy considered herself accountable to the Arab nation generally, and Arab women specifically. In August 1911, she spent her summer at the Green Cabin in the Lebanese village of Dhour Chouier [64] to write and spend time by herself [65]. In honour of her writings during her stay, a ceremony titled, “The Green Cabin Ceremony” was conducted in the village [66]. In her speech at the ceremony, Mayy Ziadeh held her achievements accountable to the feminist movement and references the irony of being honored for her writings even though she is not well-versed in the Arabic language:

وأنّي لي البلاغة، أنا التي يتعثّر لساني في اللفظ العربي البسيط؟

How can I be eloquent, I whose tongue has difficulties with simple Arabic pronunciation? [67]

Mayy’s entire speech at the Green Cabin after being honoured for her writings after staying at the Lebanese villiage of Dhour Chouier to write. August 1911.

References

[1] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Warda al-Yaziji”, 7,37-38.

[2] Ibrahim Nasrallah, Emily Adeebat Lubnaniyyat, Beirut: Dar al-Rihanyy (undated), 13.

[3] Khaldi Egypt’s Awakening, 4.

[4] Ghorayeb, Rose. “May Ziadeh (1886-1941).” Signs 5, no. 2 (1979): 375; Fatouh, Isa Adeebat Arabiyyat: Sayron wa Dirasat (1). (1994): 179; Ibrahim Nasrallah, Emily Adeebat Lubnaniyyat, Beirut: Dar al-Rihanyy (undated) 121.

[5] Jaber, Jamil “Introduction” in Ziadeh, Mayy Rasa’il Mayy (From Mayy’s letters) Beirut: Manshourat Maktabat Beirut (1951), 7.

[6] Khatib Tareekh Tatawor al-Haraka, 79.

[7] Isis refers to the ancient Egyptian goddess, and Copia, translating to abundance, is a translation of her name. May, meaning queen, Ziadeh, meaning abundance. Amongst other definitions, Mayy Ziadeh’s other pseudonym, Aida, means “returning” in Arabic. She used this pseudonym along with the masculine name Khalid Rifa’at in her early magazine publications. Her second (1912) and third (1913) books are Arabic translations of French and German novel by Max Muller Deuche Liebe (Ibtisamat wa Dumu, 1912) and the Scottish novel by Arthur Conan Doyle The refugees (al-Laji’un, 1917). Khaldi Egypt’s Awakening, 5. In September 2022, Egypt successfully repatriated a smuggled statue of Isis from Switzerland. State information service. “Egypt recovers “goddess Isis” statue from Switzerland”. September 27 2022: https://sis.gov.eg/Story/171701/Egypt-recovers-goddess-Isis-statue-from-Switzerland.

[8] Khatib Tareekh Tatawor al-Haraka, 79.

[9] For example, Mayy Ziadeh published biographies of Warda al-Yaziji and Bahithat al-Badiyya after their death..The biographies include speeches and letters she delivered in their honour. Ziadeh, Mayy Warda al-Yaziji (1924); Ziadeh, Mayy Bahithat al-Badiyya (1920).

[10] Fatouh, Adeebat Arabiyyat, 180.

[11] Prominent Palestinian feminist Sadhij al-Nassar was central in the production of the magazine, a special section was dedicated to the topic of women. al-Nassar also led the Haifa women’s Union. See: Fleischmann, Ellen. “The emergence of the Palestinian women’s movement, 1929-1939” Institute for Palestine Studies vol. 29 (1999/2000): 6.

[12] Nasrallah, Adeebat Lubnaniyyat 147.

[13] Ibid. Her library and many of her writings in Egypt were lost and she never retained possession for them. Upon returning to Egypt, she made due with the little finances she had and moved multiple apartments. Ghazali, Pascale “Rihlat al-bahith ‘an Mayy” (my journey searching for Mayy) in al-Moqawama al-Jandariyya (Gender Resistance). Beirut: ACSS (2020) 101.

[14] “Biography of Mayy Ziadeh” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. https://www.palquest.org/en/biography/33400/may-ziadeh

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] al-Saadawi, Nawal. “May wa Scheherazade”. Rose al-Yousef, May 21, 1999: 15. Appears in al-Saadawi, Nawal. “Qadayya al-mara’a wa al-fikr al-siyasi” (2001) digitized by Hindawi in 2018.

[19] Nawal al-Saadawi wrote that it was not uncommon for Mayy Ziadeh to have only men guests attend. That said, I want to complicate this belief as evidence shows that women did indeed regularly attend her meeting also, as found in a letter exchange between Egyptian feminist Huda al-Shaarawi and Mayy Ziadeh. Mayy Ziadeh had a strong relationship with the women’s movements, although she frequented as a speaker and contributor, she never formally joined a feminist union and preferred to identify as an independent writer. Found in American University of Cairo “Huda al-Shaarawi archive”, Correspondence Political and Feminist Counterparts and Colleagues, letters with Mayy Ziadeh. Box 1. According to Khatib only four women attended including Huda al-Shaarawi and Bahithat al-Badiyya. Khatib Tareekh Tatawor al-Haraka, 80. I have not yet found information on who may have helped her organize and host these large gatherings.

[20] Saadawi, “May wa Shahrazad” in Qadayya al-mara’a wa al-fikr al-siyasi, 89.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Mayy Ziadeh Street, Beirut, Lebanon. Google map https://maps.app.goo.gl/LXyfngw9CjuzMwvh9 ; Haidar, Ramzi. “A statue of Lebanese poet Mayy Ziadeh” Getty Images. Photograph: https://www.gettyimages.dk/detail/news-photo/statue-of-lebanese-poet-may-ziadeh-is-pictured-after-it-was-news-photo/90353379

[23] Mahmoud, Sayyid. “May Ziade’s writing on women’s education are republished”. Al-Fanar media. Sep 3 2021 <l https://www.al-fanarmedia.org/2021/09/may-ziade/>

[24] Mayy, “Ayn Wattanyy” [Where is my country] in Al-moalafat al-kamilla [the complete works of Mayy Ziadeh], 364.

[25] Khaldi, Egypt’s Awakening, 122; Ziadeh, Mayy Bahithat al-Badiyya/Scholar of the dessert (1920).

[26] Translation by Khaldi, Egypt’s Awakening, 169.

[27] Nassif, Malak Hifni. Al-Nisa’iyyat (1910) 145 Digitized by Hindawi (2014). Translation by Khaldi, Egypt’s Awakening, 167.

[28] Translation in Khaldi, Egypt’s awakening, 170. Original Arabic in Original Nassif, Malak Hifni. al-Nisa’iyyat, 201-102. Khaldi offers a collection of translated letters in her the appendices of her book Egypt’s Awakening in the Early Twentieth Century 159-181.

[29] Ibid. Bahithat al-Badiyya is translated from Arabic to English in a few variations including: Dessert Seeker; Scholar of the dessert; Searcher of the dessert”. I use ‘scholar of the dessert’.

[30] Translator’s word choice.

[31] Malak Hifni. al-Nisa’iyyat, 145. The book includes records of previously published letters and articles.

[32] Khatib Tareekh Tatawor al-Haraka, 79.

[33] Ziadeh, Mayy. Bahithat al-Badiya: A Critical Study. Nawfal Institute, n.d.

[34] Malak Hifni. al-Nisa’iyyat. see: Naccach, Nessrine. May Ziadé, pionnière téméraire du féminisme oriental (May Ziadé, daring pioneer of Eastern feminism). 2019.

[35] A person from Bilad al-Sham.

[36] Ziadeh, Mayy. Warda Al-Yaziji (1924).

[37] Badran and Cook Opening the Gates, 240.

[38] Ibid, 7.

[39] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Warda al-Yaziji”, 7,37-38. English translation by Miriam Cooke. Ziadeh, Mayy (1924) in “Opening the gates”, 240-243.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ziadeh, Mayy. Warda Al-Yaziji (1924), 62.

[42] Ibrahim Nasrallah, Emily Adeebat Lubnaniyyat, Beirut: Dar al-Rihanyy (undated), 13.

[43] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Bayn al-adab wa al-sahafa” [Between literature and journalism] in Sawanih Fatah (1922) 33. Essay in the book is dated 1916.

[44] Percy White was stationed by the British Government in Egypt to teach English Literature at the University. He later worked as part of British Intelligence. ”Author: Percy White” A database of Victorian fiction https://www.victorianresearch.org/atcl/show_author.php?aid=3025

[45] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Bayn al-adab wa al-sahafa” in Sawanih Fatah, 33.

[46] Mayy Ziadeh recommends to Percy to read the work of Warda and Yaziji and Malak Hifni Nassif. Ibid, 34.

[47] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Bayn al-adab wa al-sahafa” in Sawanih Fatah, 34.

[48] Al-Kuzbari, Salma al-Haffar. May Ziadeh wa-Ma’sat al-Nubugh (1987), 138.

[49] Al-Kuzbari, Salma al-Haffar. May Ziadeh wa-Ma’sat al-Nubugh (1987), 136.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Khaldi, Egypt Awakening, 127.

[52] Mayy’s home was at the top floor of the renowned Egyptian Newspaper al-Ahram it overlooked the Al-Lawaa Café. Khaldi, Egypt Awakening, 73; Khaldi, Boutheina. “The Ambivalent Émigrée: Mayy Ziyādah’s Rhetoric of Nationhood.” Journal of Arabic Literature 47, no. 3 (2016): 271; Ghorayeb, Rose “May Ziadeh” Signs: journal (375-376); 271.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ghorayeb, Rose “May Ziadeh” Signs: journal (375-376); Khaldi, Boutheina. Egypt awakening in the early twentieth century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. (2012): 271.

[55] Khaldi, Egypt Awakening 2.

[56] Khaldi, Egypt Awakening, 127.

[57] Fatouh, Adeebat Arabiyyat,182.

[58] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Bayn al-adab wa al-sahafa” in Sawanih Fatah, 34.

[59] Lutfi al-Sayyid is noted to have been her instructor that helped Mayy Ziadeh in her early days of self-mastering of the Arabic language. Khatib Tareekh Tatawor al-Harak, 79.

[60] Translation by Khaldi with edits by Mariam Karim. Khaldi, Egypt Awakening, 4.

[1] Ziadeh, May “Letter to Yaqqub Sarruf” 161-162

[2] Robinson “Syro-Lebanese Women’s Transnational and International Collaborations at the League of Nations”, 482.

[3] Ziadeh, Mayy, “Warda al-Yaziji”, 7,37-38. English translation by Miriam Cooke with modifications by Mariam Katim. Ziadeh, Mayy (1924) in “Opening the gates”, 240-243.

[4] Home to one of the first printing presses in Syria and Lebanon, the village of Dhour Chouier was frequented by visitors due to its mountainous sea views and location, adjacent to the main route between Beirut and Damascus.

[5] Zaideh, Mayy. “Haflat Koukh al-Akhdar” 9-11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ziadeh, “Haflat Koukh al-Akhdar” 9-10. She gave this speech during a writing residency in ‘Duhur al-Shuwayyir’ Lebanon in August 1911. Zaideh, Mayy. Al-Amal al-Kamilah Beirut: Mo’sasat Nawfal, second issue 9-11. Translation by Khaldi with edits by myself in Egypt Awakening, 174.

[8] Khaldi, Egypt Awakening, 128.

Cite this page:

Karim, Mariam and Al-Mohammed, Maryam. “Mayy Ziadeh and Arabic Language Media.” Nasawiyyah: Arab Media History, 2025, <https://www.nasawiyyah.com/mayy-ziadeh>